Infrastructures of Resistance: Anticolonial Education and Practices

Disobedience. In a village council election, she “Ni” voted for a candidate who is a member of a different family and political party.

Rejection. When the Minister of Education offered an appreciation letter to compensate for the fact that his corrupt staff gave the job that she created for herself—with dedication and lots of sweat—to a man from another community, she “Ik” rejected any fig-leafing for the theft.

Defiance. In the morning, a few hours after the nightly raid of her house by the Zionist army, turning it upside down and arresting her husband, she “Wa” refused to cancel the work-related public gathering scheduled to take place in her garden.

These are a few of many acts of quotidian resistance—to social pressure, to the PA’s corruption, to Zionist violence and destruction—that we witnessed while conducting the “Takhayali Ein Qiniya” project.[1] These acts are part of an ever-growing mosaic of undertakings that enable sumud and inspire ishtibak;[2] actions by strangers and friends, courageous people, several of whom have paid the heavy price of prosecution, incarceration, and torture by either the Zionist colonial authorities or the Palestinian Authority or both. Palestine does not lack initiatives of resistance—big and small, individual and collective–by the people who are the salt of the earth.

What Palestine suffers from is the in-house fending (consciously and otherwise) of the paradigms and power hierarchies created through the Oslo Agreements by those benefiting from the status quo. It is not only the PA and Fatah’s officials and their clans, but also the old and new bourgeoisie.[3] Owners of big companies that enjoy monopolies, tax exemptions, and cheap acquisition of and profiting from public assets. Numbers of doctors (health), lawyers (justice), among other professionals who make fortunes by evading taxes and rejecting regulation. Heads of NGOs who spend millions in budgets for protecting and reporting on human rights, gender equality, development, and so-called democracy; yet, in their responses to the unprecedented violence and abuses, they are overwhelmingly silent and at times complicit in silencing; not the least, against our brethren Gazans who are stranded in the West Bank. These and other categories of bourgeoisie do not form a reliable infrastructure for either a revolution or a progressive state project to emerge from, and as our friend Omar Jabary Salamanca says: “resistance is not an event, it is an infrastructure.”[4]

After three decades of the illusion of the two-state solution and state building á la western recipes, which have yet to prove successful anywhere in the world, we need to break the cycle. The retraction of ODA (official development aid) in favor of armament is a death blow to millions of people around the world. The tragedies befalling all these many communities are a wake-up call and a window to finally take the leap, to coalesce serious efforts working to reconfigure the artificially created dependencies and vulnerabilities. Although activists, artists, and intellectuals in Palestine have been talking about disengaging from conditioned funding for more than two decades, sadly we are not ready, and the same applies to systems of patriarchal hegemony and suppression of any critique that exceeds rhetoric.[5]This is due to several factors, at the core of which, lying front, center, and periphery, is the dwarfed spaces of dialectical and reflexive education and curiosity for investigation.

Time does not go back, and the conditions that enabled the progressive socio-political revolution of the 1970s and 1980s in Palestine have ceased to exist; be that the intimate scales, the relative ability to move around most of our land (pre-cantonization), the comparable equality of all under the boots of the colonizer. Among other critical dimensions, there were several (not only two) strong political parties that, combined, provided hundreds of loosely coordinated yet well-organized frames and subframes that blew winds into the sails of voluntary love-driven initiatives.This was enabled through hope-engendering socialist pedagogies of enablement that genuinely believed in the power of the individual, and community co-funding (e.g., cooperatives). The mass mobilization into organized disobedience, rejection of, and defiance against the colonizers was possible because the overwhelming majority of Palestinians saw themselves as elemental in the collective discourse.[6]

Children, young, middle-aged, and elderly, differently abled majorities of females and males and gagged genders in each ‘nucleus’ (sub-community) supported farmers against land confiscation (food sovereignty) and built classrooms of bricks, or wild shrubs, or prison walls (education). They inhabited transient places in antispaces[7] where the compass of an outstanding generation of educators was not fulfilling a curriculum or any requirement, but the mission to create independent, proactive thinkers who can imagine otherwise and keep communities safe, connected to each other and to their land. It was hundreds of educators, mentors to and conversers with hundreds and thousands of trainees turning comrades. The social practices and networks of the time enabled connecting formal and informal education with threads of timely experiments to address concrete economic, social, and environmental issues in material spaces. They built contemporary societal knowledge that is rooted in context, in challenging the evolving Zionist technologies of incarceration, while advancing liberatory legacies like those of Khalil Sakakini and Fu’ad Nassar. Some of these practices still exist, and we sensed that in our work in Ein Qiniya.

For us as Palestinians, genocide is no longer a term linked to the worlds between the Nakba and the summer 2014 war, such as the Kafr Qasim Massacre or Sabra and Shatila, to name just two. Since a year and a half ago, genocide has become daily breakfast and dinner; today it stands as a possibility for every Palestinian doorstep all across historic Palestine, and lest we ignore that since seven months ago it reached Beirut and on its tails Damascus. May we remember that the drums for the Gaza Strip’s ongoing genocide started in the Armenian Nagorno-Karabakh (relatives of some of the best Palestinian artisans since about four centuries ago), and are paralleled in Sudan (relatives of some of the Palestinian guards of Bab alMajlis, one of the gateways to alAqsa Mosque). During the first months of “genocide at home” we were paralyzed by Qahr[8] as we became unwilling witnesses to a long-plotted, expanded erasure scheme. Gazans asked us not to get used to it, yet here we are. Neither the atrocities in the Gaza Strip, Yemen, and Lebanon, nor those in the refugee camps in Jenin and Tulkarem, nor the overwhelming poverty throughout the West Bank have nudged the realities in what in effect are test grounds of AI surveillance and an Egypt-style police state, and further, we are still failing to topple the new “temporary” status quo of daily erasure on steroids.

With view to the aforementioned, imagination in the highly militarized geography and amidst the ongoing genocide is a very hard act, yet it is a crucial one. It is an act where one reconstructs images in familiar or unfamiliar compositions; it is part of habituating and enduring, looping and intensifying catastrophes through everyday routines of survival and resistance, of sumud and ishtibak. Imagination is not escapism; it is a rejection of dispossession and a defiance of oppression through reconstruction and reconfiguration of spaces, places, and relations; and therefore, it is part of struggles against erasure both fast and slow, against the paralyzing, always imminent threat of displacement and loss of everything. Imagination is a vital practice for persons deprived of the right to shape their futures, to keep up the hope and to keep seeking it. It is a moment of reflection and socialization among local, translocal, and diasporic communities, creating adhesives around shared visions of a future that transcends past and present horrors.

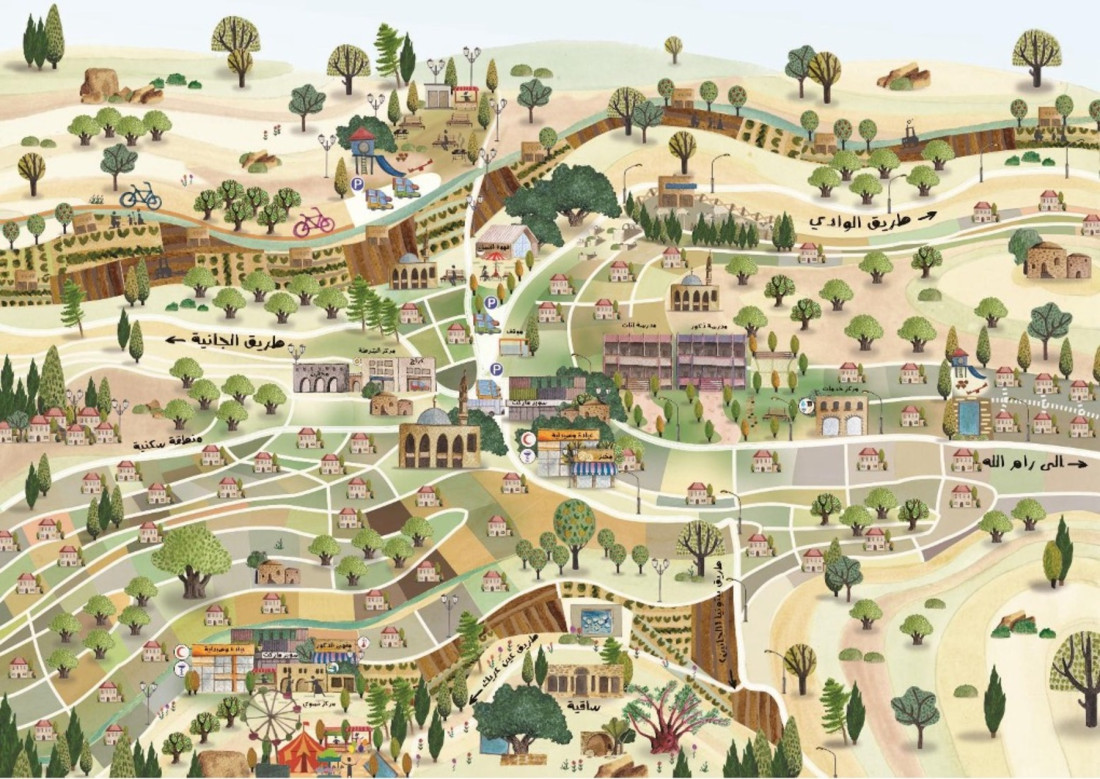

At the beginning of this essay, we mentioned the Takhayali [imagine, fem.] Ein Qiniya project, which we implemented guided by principles and issues named earlier. It was the product of a village, through 20 of its women who crafted imaginary masterplans based on each one’s perceptions of the daily challenges and needs (two years ahead of the commencement of official procedures), as well as several other women, men, and many children who positively engaged with and influenced the research in different ways along its four years of fieldwork (2018–2022). The central theme for the team’s work was gendered infrastructural violence. Investigations utilized the space of the research to collectivize questions about potential and desired spatial refiguration and reconfiguration through a two-legged approach: (1) Small-scale immediate activities (themed workshops, acquiring funding for and establishing a Resources Room at the village’s school after two interlocutors envisioned it in their masterplans); and (2) Futuristic explorations of ideas and production of artifacts to provoke public debate on what constitute “public interest” in terms of urban regulations in areas administered by the Palestinian Authority (20 Imaginary Masterplans for Ein Qiniya, “Takhayal/i alWadi” short film, short and long texts).

The project was a temporary space for individuals, collectives, and institutionalized entities, whose actions—acts performed out of deep belief, love, modesty, and connection to the land—threaded longer social and ecological histories, and drew the contours of tacit community knowledges in moments that escape capture but are the essence in enabling continuation in spite of the grim odds. The project’s material and immaterial outcomes are a reflection of the support of many families, friends, and acquaintances. It was a slow process, deliberate, rooted in care for people before academic targets, adapted to the shifts in the conditionalities of the field and those of involved persons. It remained open to changing course, to critique, to learning and unlearning. We trusted intuition and oriented with knowledge; we embraced pauses, experimentation, and mistakes. Until the very end, we questioned our methods, our feminist stances, and our positions, striving to make visible the efforts of every contributor.

Did the Takhayali research project change the harsh realities of the people of Ein Qiniya? No, it did not; however, it gathered old community knowledge to create new ones, new initiatives; it left a slight improvement in the infrastructure, and many hope-generating memories of genuine solidarity through social practices of those who engaged with the project, and who give us belief in the possibility of emergence of rooted, new anticolonial practices.

This article was written by Mai alBattat and Natasha Arur.

Mai al-Battat is an architect and researcher focused on countermapping as a medium for spacio-political urban investigation and resistance practices.

Natasha Aruri’s work focuses on spatial politics of and resistance to (neo)colonialism, community-based research methods, and the intersection of critical mapping and social mobilisation in prompting spatial transformation.

Photo: Masterplan by Fareeda (Um Qarawi), canvas A1, 2022. Fareeda spoke about the need for economic security and emphasized that Ein Qiniya’s agricultural production along its two wadis (water streams) is an asset that should be maintained and improved. Process: sketching, watercolor, digital assembling by Mai Al-Battat. Visual production assistance by Yara Bamieh and Basel Naser.

References:

[1] “Takhayali Ein Qiniya” is the cornerstone of the larger “Takhayali Ramallah” project (2018-2025), which is implemented by UR°bana in collaboration and partnership with several institutionalized and uninstitutionalized peers and comrades, including Sakiya, alMasna’, Amal Juma, and others. The project’s website with relevant information, analyses, and the outcomes will be launched in late summer 2025: takhayali.net.

[2] Sumud: Arabic, noun, a combination of steadfastness and perseverance. Ishtibak: Arabic, verb, to engage with something, also to engage in battle, to clash.

[3] In his work “The Wretched of the Earth” (1963), Frantz Fanon describes how the bourgeoisie tend to avoid risks, prefer investments securitized by coincidence with colonial interests, and refrain from staging a challenge. For Fanon, one of the main problems of the bourgeoisie lies in their incapacity to conceive new worlds, where it “is lacking ideas, because it is inward looking, cut off from the people, sapped by its congenital incapacity to evaluate issues on the basis of the nation as a whole” (ibid:102). Therewith, in practice they are subsidiary managers in colonial economies rather than revolutionary entrepreneurs.

[4] During a presentation in the panel “Voices from Palestine: Decolonization in Practice” (organized by Arab Urbanism on 21 May 2021, online) and as he connected several of his analyses on the role of infrastructure, Omar Jabary Salamanca said and expounded on his phrase “resistance is not an event, it is an infrastructure.”

[5] See: Toufic Haddad’s Palestine Ltd. Neoliberalism and Nationalism in the Occupied Territory, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018.

[6] E.g., Women, ofttimes analphabetic, were the keepers of secret safe houses, knit sweaters for prisoners and those in hide-outs, and served and cared for thousands during political rallies; children were the watchers sounding the alarms to older youth when the Israeli army approached, the messengers, and they re-locked shops after the army broke doors.

[7] In his book “Finding Lost Space: Theories of Urban Design,” Roger Trancik writes that unshaped antispaces emerge from the urban development processes that treat “buildings as isolated objects sited in the landscape, not as part of the larger fabric of streets, squares, and viable open space […] and without a real understanding of human behavior.” (1986:1). That said, besides this western definition under which one can classify all retention spaces around buildings in Palestinian communities; in our view, in anticolonial geographies antispaces are also those utilized in ways other than the function ascribed to them, in order to forge dissent to hegemony.

[8] Qahr: Arabic, noun, a combination of sentiments spanning wrath, indignation, grief, frustration, helplessness, defeat.

Mai al-Battat

An architect and researcher focused on countermapping as a medium for spacio-political urban investigation and resistance practices. She is currently a research assistant and coordinator at the Ibrahim Abu-Lughod Institute of International Studies, Birzeit University. She worked as a researcher with UR°bana in the multisite research project “Urbanization, Gender and the Global South” (2018-2024).